Contract Farming: Our Way in as “New” Entrants

I don’t necessarily want to describe us as “new entrants”, but as we don’t own a farm and haven’t inherited a tenancy in some ways we are. I grew up on a family farm and my partner grew up on a smallholding with a small flock of sheep and a handful of Welsh Black cattle. However, neither of us farm with our families and nor have we inherited land or animals. I once read an American woman describe herself and her husband as “first generation farmers with family history” which is probably the best label we could apply. Regardless, apart from experience and our two cows Claudia and Jane (gifted from my father) we are new entrants- at least where capital is concerned.

Our business structure influences our farming as we are running the farm in a working relationship with the farm owners rather than it being solely ours. When I talk about or write about the farm I’ll often mention the set up as it underlines everything we do, so I better start by explaining how it works.

With Claudia, the first heifer calf born to one of our owned cows

Much of the discourse on new entrants into agriculture focusses on access to land- understandably- and has an emphasis on the ability to buy farms or secure tenancies. Given the capital hungry nature of both of these pathways, entry into agriculture is often regarded as unattainable. This is especially the case with dairy farming. Whereas a wannabe sheep farmer can make a start with a small flock, a dog, mobile handling, and a grazing licence, dairy farming at a small scale struggles to be profitable (but has a daily labour requirement that makes it harder to seek other work than sheep farming does) and relies on infrastructure (parlour, sheds, machinery, milk cooling) that is beyond the reach of many young people.

The lump sum exit scheme offered by DEFRA focusses on farmers vacating their farms through either selling their land or renting it out. The alternative- which arguably offers more opportunities for new entrants than either land purchase or tenancies- doesn’t fit into the scheme because it retains the landowner as the active farmer. I’m talking about contract farming, the business structure which has allowed us to have a farming business.

Contract farming is not new. There are references to share farming agreements dating back centuries and it is a recognised legal entity in Australia and New Zealand. In the UK share farming has no status and can fall under rules regulating partnerships, which is why we instead have a contract farming agreement, which is based on us as the contractors having a contract with the landowners, who are referred to as the farmers.

Our CFA is run by the farm’s consultant who works for the same company as I do. He meets us once a year to review the previous year, work out the divisible surplus, and check that our budget for the new year looks sound (yes, in these meetings I get scrutinised as a farmer AND as a consultant- sometimes I think I should bring along a recently written feature and mobility score a few cows just to get a full portfolio career assessment).

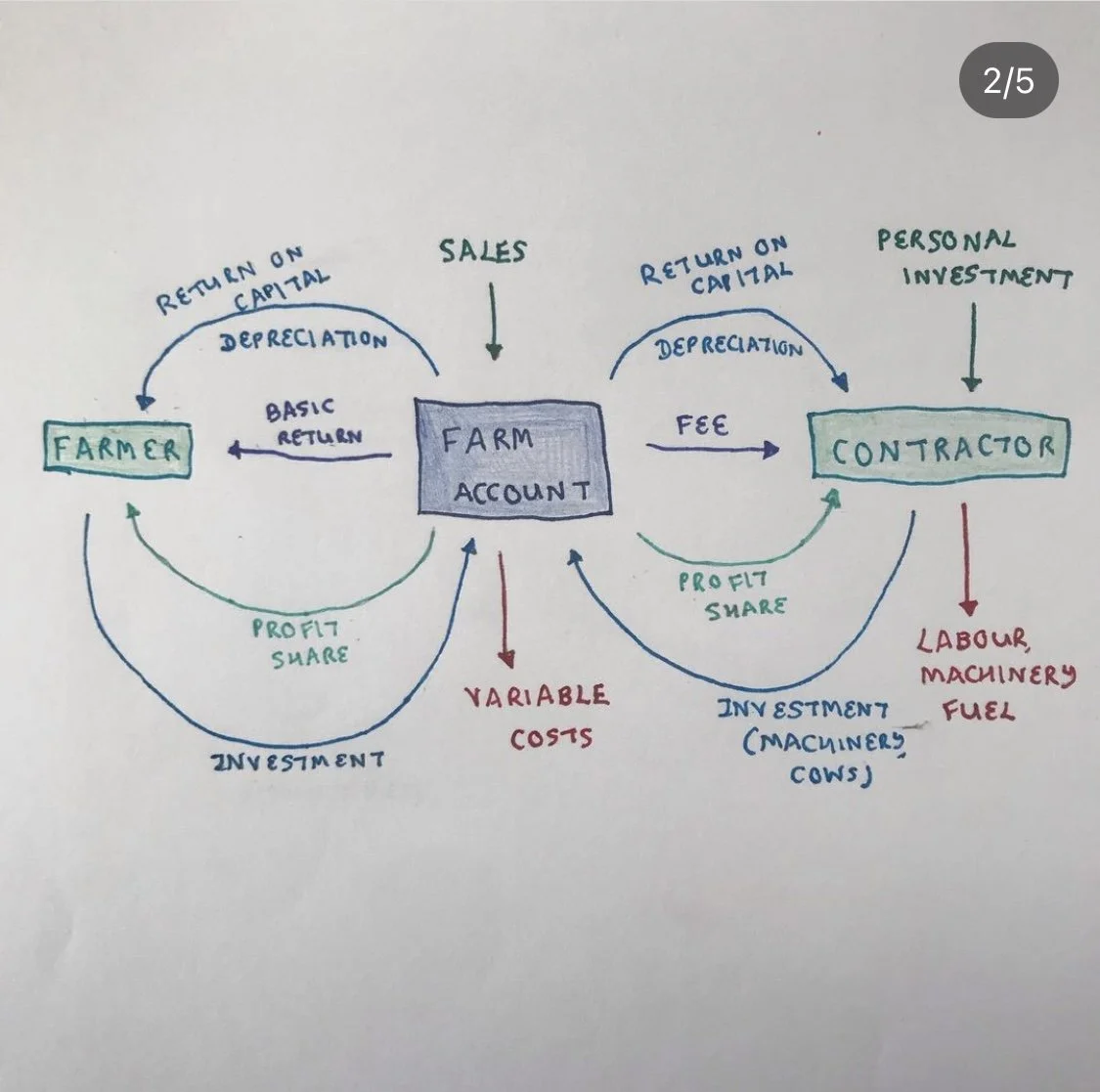

My partner signed the first CFA here in 2018, and I bought a share in his company and we signed a new CFA in 2021. Our company is contracted to manage the farm, and in return we receive a monthly fee that covers labour, machinery repairs, machinery depreciation, fuel and oil, and the cost of external contractors used for tasks such as silage making, hedge trimming, slurry spreading, and re-seeding. We receive a Return on Capital payment for the machinery and any cows we own on the farm, as do the farm owners. They also receive a depreciation fee for the infrastructure they supply and a rental equivalent for providing the land.

One bank account- owned by the farm owners- receives the milk cheque and any livestock sales and pays the usual dairy farm costs (feed, fertiliser, electricity, minerals, farm repairs, dairy chemicals etc), our contracting fee, the rental equivalent, and the depreciation and RoCs. At the end of the year the surplus is split between us and the farm owners in an agreed ratio.

A diagram showing the cash movement in a CFA

So why is a CFA sometimes an easier and better option for new entrants? CFAs allow access to farming with comparatively little capital. In 2018 our company purchased half of the machinery used on our low input spring block calving herd. Compare that cost with the cost of setting up a new tenancy- supplying an entire machinery fleet (or financing it), buying a herd of cows, and potentially investing in infrastructure if the farm wasn’t set up or the landlord wasn’t prepared to make that investment. From that first year we received a RoC for having that machinery, and were able to invest our surplus share back into the agreement by buying the rest of the machinery and increasing our RoC.

Once the machinery is purchased most agreements then have scope for the contractor to buy cows- this usually starts as a portion of the herd and in some cases is capped as the farm owner wants to retain some cow ownership.

Gradually the contractor has the opportunity to increase their farming capital through investing their share of the farming profit (what we call the “divisible surplus”- profit sharing is a banned phrase in contract farming agreements as it implies a different business structure). Clearly this is a great incentive to work hard and be profitable but it is also a sustainable way to grow your business.

This also means that should it be your goal the contractor can come to the end of their contract with a machinery fleet and a herd of cows to hand- exactly what you need to stock a tenanted farm! While you’ll need to be a good farm manager to secure a CFA in the first place you’ll also learn a huge amount while doing it, meaning that you’ll have the skills and the capital to fly in future endeavours.

There are other benefits to contract farming too. Having a farmer in place who knows the herd, the land, and has years of experience managing the farm makes running it less daunting than turning up one day and having to figure it all out from the bottom. The support of the farm owner is overlooked in a lot of these discussions but can be invaluable. And CFAs really do depend on the farmer and contractor having a good relationship. There’s a lot of trust in both directions.

Sometimes it can be frustrating seeing other people the same age as us who have inherited brilliant family farms with established and profitable businesses and the balance sheet to invest in infrastructure upgrades as and when they choose. Being on this side has made me very aware of the entitlement that so many of our peers have- its astonishing how much people who stand to inherit millions of pounds of assets and profitable businesses can complain about their lot!

However I’m really glad we’re doing it this way. We are extremely lucky to have this opportunity as CFAs are still not that common, especially in West Wales where the culture is for small family farms. It’s an unbelievable privilege to be able to do this, and it means that we can build our own business and shape our own future. Everything we do is on the basis of our own hard work (with a bit of luck and thanks to the people we employ and work with). Being able to bring in my partner’s experience working on a CFA farm in England and my knowledge base from consulting and my family farm gives a broader perspective, and the structure of the CFA makes everyone involved focus on the farm as a business.

In the future I can see CFAs becoming more common. They are an attractive option for landowners as they allow you to retain your active farmer status, maintain a farming interest, and get the reward of helping someone start their farming career.

I certainly wouldn’t be farming without this opportunity and would never have dreamt that there could be a way to be a farmer without inheriting a farm or (eye roll) marrying someone who stood to do so. Unfortunately a lot of people aren’t aware of CFAs or the amazing option they can be, but I really hope that more young people get the same chance that we have.

If you’ve got any questions about CFAs leave a comment, or email me to ask more. You can also follow me on Instagram anna.writes.farms.rides and you can enter your email address below to receive these posts by email.